Commercial projects aren’t one size fits all. By bringing in metal panel products to suit the individual need, designers and architects can provide custom solutions for a variety of applications. Single-skin metal panels and insulated metal panels (IMPs), if used correctly, can together add both aesthetic and functional value to your projects.

While IMPs can provide superior performance with regard to water control, air control, vapor control and thermal control, you may sometimes find your project requires—from an aesthetic perspective—the greater range of choices available in single-skin profiles. Let’s spend a little time looking at some of the reasons behind the growing trend of specifying a combination of insulated metal and single-skin panels.

Benefits of Insulated Metal Panels

Insulated metal panels are lightweight, composite exterior wall and roof panels that have metal skins and an insulating foam core. Their much-touted benefits include:

- Superior insulating properties

- Excellent spanning capabilities

- Insulation and cladding all in one, which often equates to a shorter installation time and cost savings

Benefits of Single Skin

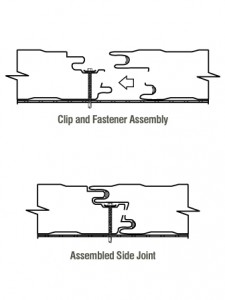

Single-skin panels, on the other hand, with their expansive array of colors, textures and profiles, may have more sophisticated aesthetics. They can be used on their own or in combination with IMPs. It should be noted, too, that single-skin panels can—in their own right (as long as the necessary insulation is incorporated) —satisfy technical and code requirements, depending on the application.

Beyond aesthetics, when it comes to design options, single-skin products offer a wide range of metal roof systems, including standing seam roof panel, curved, and even through-fastened systems. As for wall systems, those may include concealed fastened panels, interior wall and liner panels, and even canopies and soffits, not to mention exposed fastened systems. Therefore, you have a wide range of not only aesthetics options but VE (Value Engineering) options as well.

Why Mix?

So, in what situations might the designer or architect choose to combine the two panel types? Let’s examine a couple of specific scenarios related to the automotive or self-storage worlds as a means of illustration. In both of these types of applications, it is not uncommon for the designer to recognize the importance of wanting to keep the “look” of the building consistent with branding or to bring in other design elements.

Single-skin panels can be used as a rain screen system in the front of the building or over the office area, and would provide the greater number of design options. In the rest of the building, designers can take advantage of the strength, durability and insulation benefits of IMPs. Although you could use one or the other for these examples, the advantage of mixing the two would be achieving a certain look afforded by the profiles of single-skin, while still adhering to stringent building codes and reducing installation time—which is the practical part of using IMPs.

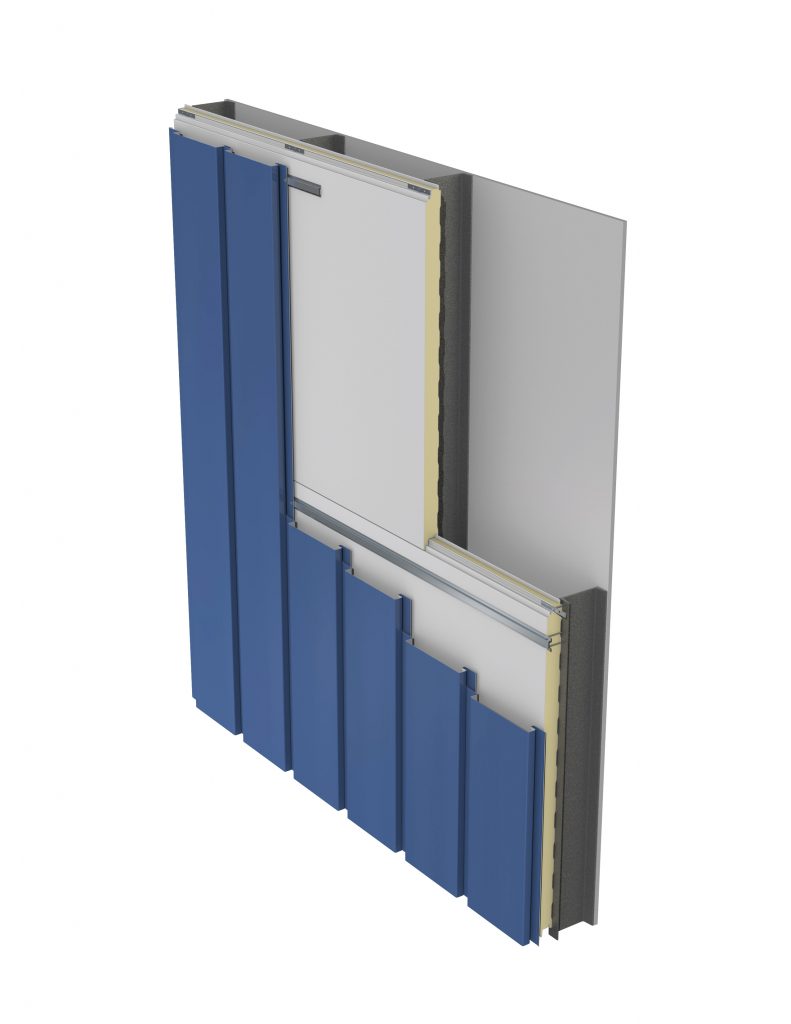

Focus on HPCI IMP Systems

One great example of a current trend we’re seeing at MBCI is the use of the HPCI-barrier IMP system, along with single-skin panels. The High Performance Continuous Insulation (HPCI) system is a single system that is a practical and effective replacement for the numerous barrier components found in traditional building envelopes.

A big benefit to using the HPCI system is that the barrier wall is already in place. In terms of schedule, the HPCI barrier system is typically installed by contractors who are also installing the single-skin system, eliminating the need for multiple work crews, and thereby minimizing construction debris and reducing the likelihood of improper installation. With a general lead time of four to six weeks for the HPCI and a week or two for the single-skin, the installation goes fairly quickly. Therefore, it appeals as the best of all worlds—a single system meeting air, water, thermal and vapor codes (ex.: IBC 2016, NSTA fire standards) plus the design flexibility of a single-skin rain screen product. (Note: The HPCI panel must be separated from the interior of the building by an approved thermal barrier of 0.5″ (12.7mm) gypsum wallboard to meet IBC requirements.)

Bottom line, HPCI design features and benefits include the following:

• Provides air, water, thermal and vapor barrier in one step

• Allows you to use multiple façade options while maintaining thermal efficiency

• Easy and fast installation, with reduced construction and labor costs

Conclusion

As designers, architects and owners are getting smarter about a “fewer steps, smarter dollars” concept and an increased awareness of applicable codes and standards, not to mention lifecycle costs, the trend towards maximizing the strengths of available systems will continue to grow. Whether the right choice is an IMP system, single-skin or some combination, the possibilities are virtually endless.

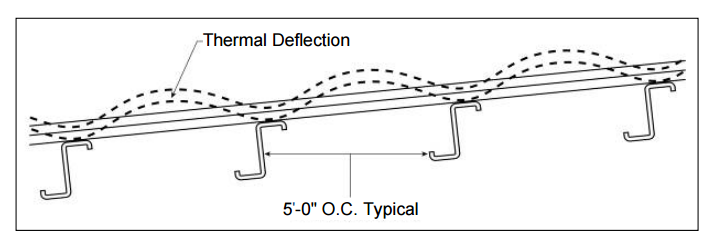

In fact, engineered metal panel systems offer arguably the best possible continuous exterior system. Not only are they properly applied exterior to the building structure—outboard of columns, joists and girts—but they are also designed to ensure an

In fact, engineered metal panel systems offer arguably the best possible continuous exterior system. Not only are they properly applied exterior to the building structure—outboard of columns, joists and girts—but they are also designed to ensure an