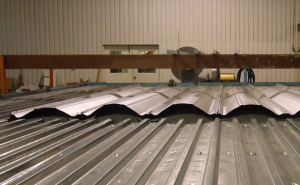

Breaking away from simpler panels, more and more architects are experimenting with arched and curved metal roofing and wall panels to upgrade their designs. This enables designers to incorporate exciting elements like concave and convex curving, not as feasible with other cladding materials.

Combined with unique angles, increased edge finishing options, appealing gutter options and greater compatibility with shingle types, architects now have access to a greater assortment of mix-and-match options.

For example, at Owens Community College in Findlay, Ohio, a regal red, double-curved canopy crowns the curtainwall with 15,500 square feet of 22-gauge curved metal roof panels. Designed by Rooney Clinger Murray Architects, the structural roofing panel system, fabricated by MBCI, is ASTM tested for air infiltration and water penetration, and incorporates a 2-inch tall standing seam that was field seamed during the installation process. The contractor, Charles Construction Services, won the American General Contractors (AGC) Build Ohio Award for “New Construction Under $10 Million.”

Another noteworthy curved design example is the Central Los Angeles Area High School #9, designed by HMC Architects. “Metal enabled us to clad buildings of different geometries, including curved geometries, in one material, while also giving them a special appearance,” reported Kerstin Kohl, spokesperson for the project’s design architect, COOP HIMMELB(L)AU, in a Metal Construction Association case study, Steeling Art for Students.

Using CAD and BIM for Curved Metal Panels

For designing and fine-tuning curved metal creations, the latest CAD and BIM features are key tools for architects.

In creating the “geometry that has been freed from the relentlessness of the orthogonal layout,” as described by Mark Dewalt, AIA, principal at Valerio Dewalt Train, in a recent article in Metal Architecture magazine, New Trends in Metal Architecture, designers are using CAD in shop drawings to support unique façade fabrication.

“The use of computer design to warp and twist and perforate will give metal greater longevity, added Kevin Marshall, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, associate architect, Integrated Design Solutions.

Similarly, BIM software is further supporting enhanced compatibility with metal roof and wall designs with newer features such as automated light gauge steel wall framing work and the ability to more easily configure supporting structures, openings, complex L or T connections and service hole positions while providing photorealistic renderings so that the client can see exactly how their building will look once built.

Ensuring a Tight Building Enclosure with Curves

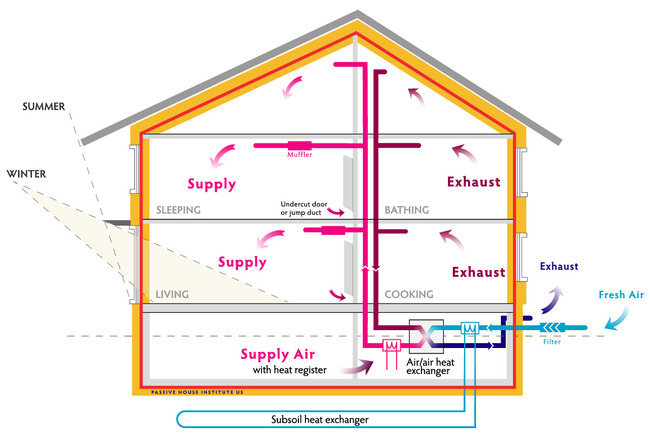

As with any roofing type, designing and installing a tight building enclosure for curved roofing and walls is essential for delivering a high performing building.

For starters, architects must choose an appropriate vapor retarder, especially in cooler climates and interior relative humidity levels of 45 percent or greater. Also, buildings with high humidity interiors and construction elements that may release moisture after the roof is installed–such as interior concrete and masonry, plaster finishes and fuel-burning heater– require special considerations when choosing vapor retarders.

With utility clips, some curved panels will lay tight to the wood deck, but if tin tabs are used to attach the moisture barrier to the wood deck, then they will need to be covered to prevent the tabs from rusting the back side of the panels. Similarly, plastic washers may not be the best option as they run the risk of impacting the panels, resulting in undesired aesthetics. Rather, peel and stick membranes are a preferred underlayment because they eliminate the potential of underlayment fasteners penetrating or dimpling the panels.

A Savvy Look for Design

Whether it’s wavy, circular or some other exciting soft geometric shape, curved metal roofing and walls open up all kinds of new design possibilities. Out of the box, literally, architects are actively producing exciting, eye-catching creations with these welcomed capabilities.