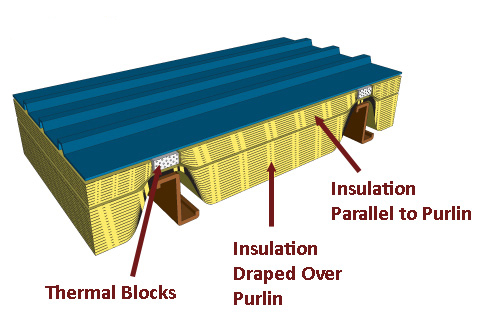

In the age of increased energy efficiency requirements in buildings, designers often find themselves spending time and resources squeezing performance out of systems with relatively little gain in efficiency. More and more, building insulation systems seem to fall into this category. The authors of the building codes recognize this as well and have reacted by turning their focus on other metrics like air infiltration where more substantial gains are to be had. A similar situation exists with lighting efficiency. However, when it comes to daylighting, designers are often pushed out of their comfort zone because lighting concepts and terminology is quite esoteric and difficult to comprehend.

m

The truth is that most people take light for granted and aren’t aware of the complexity of lighting for human activity and comfort. Probably the biggest reason for this complexity is the fact that the human eye is the only way we can judge light and although the eye is an evolutionary masterpiece, it has its own idiosyncrasies and no two eyes work identically. For instance, the typical human eye can discern shades of green at much greater accuracy than other colors and because of this sensitivity, green light is often perceived as brighter than other colors at the same energy level. Therefore, quantifying light level for human comfort and function must take this sensitivity into account, leading to some complexity. Here are some basic principles that you need to understand:

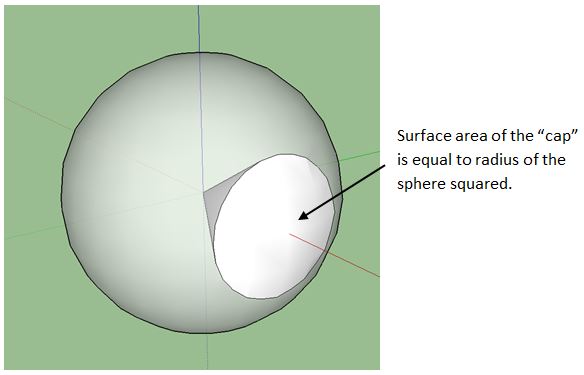

A steradian is a unit of solid angle measure. You can think of a 1 steradian solid angle as a cone cut out of a sphere with the apex of the cone at the center of the sphere and cross-section angle of approximately 66 degrees. A unique property of a 1 steradian solid angle is that the area of the semispherical “cap” captured by the cone is equal to the radius of the sphere squared. This makes it a convenient shape to use in measuring the amount of light projecting from a source at the apex of the cone through its interior and onto the cap because the amount of energy passing through any cross-section along the way is always the same. There are 4π, or approximately 12, steradian in a sphere.

Light is generated at the molecular level by the outer bands of electrons surrounding a given atom. When these electrons become excited at a high enough level, they emit a burst of energy in the form of electromagnetic radiation of a wavelength interval unique to the emitting atom in order to return to a lower energy state. If the energy level is just right, this wavelength will be in the visible light spectrum and viewed as a specific color. White light is formed when many atoms respond at various energy levels distributed across the entire visible spectrum in a pattern such that the energy transmitted is roughly constant with wavelength. The human eye is not responsive enough to discern the different colors hitting it, so an overall stimulation results in a static or “white” response. (There is a similar concept for sound as well, called “white noise”, when the ear cannot detect the individual vibration frequencies.)

The absolute brightness of light is given by the total energy it transfers through electromagnetic modulation. It is determined by summing up the energies transferred by each incorporated wavelength. As light travels from a point source, this energy spreads, causing the amount of energy arriving at a single point in space to decrease as that point is placed farther away from the light source. Brightness decreases with the square of the distance from which it is viewed. In other words, a light will appear ¼ as bright when viewed from a distance twice as far.

Because the human eye is more sensitive to green light than other colors, the brightness it perceives from different lights can only be effectively compared at the same color or wavelength. For light used for human function and comfort, it has been standardized to quantify the brightness at the 555 nanometer wavelength, which is near the center of green in the visible light spectrum, and then adjust for the effect of other colors consistent with how the human eye perceives them. Color is accounted for by weighting the energies transmitted at other wavelengths using the luminosity function. The resulting quantity is called perceived brightness. The luminosity function is similar to a bell curve and it represents how relative brightness of various colors is perceived by the typical human eye. As you might expect, the luminosity curve peaks at a wavelength near 555 nanometers.

Absolute brightness is measured in watts and should only be used when comparing lights of the same color. This should not be confused with power consumption, which is also measured in watts. Perceived brightness is instead expressed in candela and is the only way light of mixed color (on non-monochromatic) can be compared. A one candela light source with a wavelength of 555 nanometers transmits 1/683 of a watt of energy.

It is also important to be able to quantify total light output of a light source. Real-world light sources are not usually of equal brightness in all directions, so candela is not the best measurement to use. To account for spatial variation, total light output is defined as the sum total of light passing through every point in a cross-section of a one steradian solid angle, considering a light source at the apex, divided by the area of the section. This results in the same quantity regardless of the location of the cross-section. So, if a light were to transmit one candela through each point in the cross-section of a unit steradian, then it would be said to produce one lumen of light. Likewise, a 555 nanometer light source radiating one watt per steradian of energy produces 683 lumens.

Finally, the effect of light projected onto a surface must be defined, commonly called illumination level. If a light projects through a solid angle of one steradian at a uniform perceived brightness of one candela, the illumination level achieved one foot away is called a footcandle. This definition confuses many people because it is contrary to what the name might imply. But because a unit steradian is used as the basis, a footcandle equates to one lumen per square foot and it is generally much easier to think of illumination level in this way. Lux is the metric equivalent to a footcandle and there is about 10.8 lux in a footcandle. Since illumination level differences of one tenth of a footcandle are not detectable by the human eye, this is often simplified to 10 lux per footcandle.

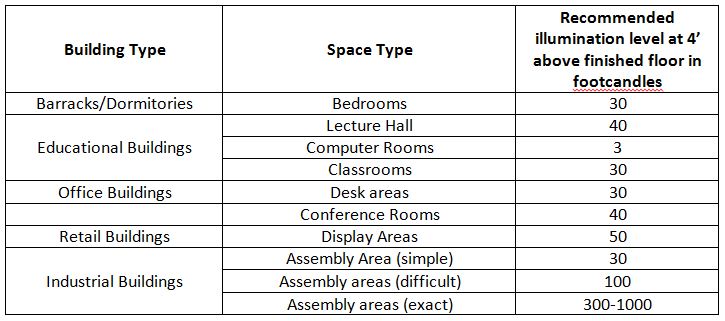

To put this all into context, a dome skylight 24” in diameter, elevated a foot above a 30’ high roof on a 20’ x 20’ grid on an open building in El Paso, Texas, achieves about 25 footcandles at a level 4’ above the floor at noon on March 21st (typical spring equinox). Compare this versus the following recommended illumination levels for various tasks as recommended by The Whole Building Design Guide:

Understanding these concepts will help you get more out of MBCI’s latest whitepaper, Shining Light on Daylighting with Metal Roofs, where MBCI explores the subject in detail, wholly within the context of metal roofs and metal wall systems. We hope you find it…err, enlightening.